It is amazing how Huisgen azide-alkyne cycloaddition, once resurrected and reinvented by K. Barry Sharpless, generated so many application papers while we are still digging to understand its copper-catalyzed mechanism.

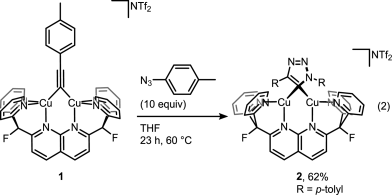

A recent JACS paper from Don Tilley lab sheds some more light on the catalytic cycle. And it’s not that easy as setting up the reaction itself. Disrupting catalytic cycle in step-by-step fashion is a tricky business but it was beautifully done in this study. First, trapping elusive cycloadduct within dinuclear copper complex:

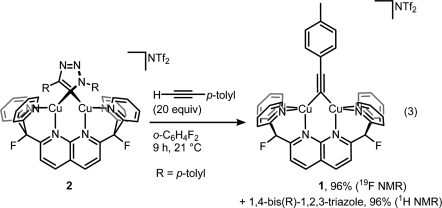

Then displacing it with a fresh alkyne to get the product and the complex ready for another catalytic cycle:

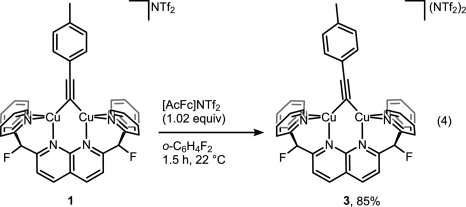

But then look at the scheme below, which is arguably the least dramatic change one can imaging from a chemical transformation (involving organic compounds).

For those still scratching their head about what did actually happen here, it’s a one-electron oxidation of Cu(I)-Cu(I) dicopper complex into mixed-valence Cu(I)-Cu(II). That slight tilt of the bridging alkyne ligand seems to be the only indicator that reaction indeed took place without much of competing disproportionation or whatever could happen to the complex. Yes, it takes X-ray crystallography to prove that, and I wonder if Micah Ziegler, the first author, a priori knew what to look for to monitor the reaction success. EPR? Cyclic voltammetry? Maybe color change was enough?[1]

Anyway, attempts to get the mixed complex 3 to react with tolylazide didn’t succeed. So authors concluded that CuAAC does not involve mixed-valence dicopper complexes. In addition, they excluded a bunch of alternatively proposed intermediates. This was in fact contradicting with earlier results published by Jin et al of Bertrand lab. The key difference between papers was that in the latest study authors forced two copper atoms to sit close to each other, while Jin et al used mononuclear copper complex to initiate the reaction [2]. This may bring up a discussion of what study is more relevant for ‘real world’ cycloaddition. I wonder more, however, if knowing the exact mechanism will help one to improve the reaction in any way. It already is pretty well-optimized and reliable (to a point).

More generally, it seems like the dissociation of practical application from (strictly unambiguous) theoretical explanation is a genuine feature of science. Take for instance CRISPR-Cas9, which leading experts are still trying to understand how it works in native systems (i.e. bacteria) while other scientists are ready to tweak human embryos with it.

[1] 19F NMR had enough difference due to different stoichiometry of triflimide anions.

[2] It still might be that both results are ‘right’ and one intermediate can turn into the other.